The year is 1983. 6 men arrive at a voting precinct in Oklahoma. The men are of varying ages and statures, but there is at least one trait that they all share. They are all black. As they approach the door of the precinct, their leader, a Reverend called Nero, issues a quick word of encouragement to his band of braves. The men steady their nerves and their resolves. Not one of them is sure what may happen next.

It only takes a few moments for it to all be over. The men return to their vehicles, not a single vote cast among them. They have been turned away from the polls this day for the simple fact that only citizens of this nation are allowed to vote. And, because they are black, these men are not considered citizens.

Though the details in the story above were imagined, the story itself is very much based on actual events that happened in these United States in the far, far away state of Oklahoma in the long ago time of 1983.

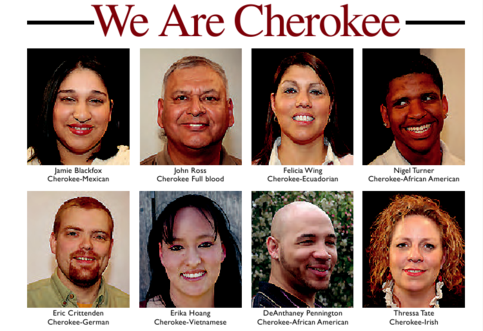

The men in the story are descendants of a little-known group of people referred to as the Black Freedmen. Once owned as slaves by wealthy and usually mixed-race Cherokees, the Black Freedmen were emancipated and granted full citizenship in the Cherokee Nation in an 1866 treaty between the Cherokees and the US government. Since then, the Black Freedmen’s story of equal acceptance into the Cherokee Nation has been a twisted one fraught with legal entanglements, questions of culture and identity, and sturdy allegations of fraud and good ol’ American racism.

as slaves by wealthy and usually mixed-race Cherokees, the Black Freedmen were emancipated and granted full citizenship in the Cherokee Nation in an 1866 treaty between the Cherokees and the US government. Since then, the Black Freedmen’s story of equal acceptance into the Cherokee Nation has been a twisted one fraught with legal entanglements, questions of culture and identity, and sturdy allegations of fraud and good ol’ American racism.

I’d really never heard of the Black Freedmen until a Facebook friend of mine shared an article from MSNBC outlining the most recent in a long history of legal battles between the Black Freedmen and the Cherokee Nation. Like many of you might have, I’d heard stories of Blacks and Natives intermarrying and having children together, but I never knew that there was an established and officially recognized group of Blacks that were considered Cherokees – by blood or by naturalization. I’d venture to say it was left out of my required history classes as a young lass.

But after reading the article, it quickly turned from a curious little historical sidenote, into a current-day political conundrum that threatens the concepts of sovereignty and democracy that define our modern government, and brings back into focus basic civil rights issues that, before now, I naively believed had long ago been put to rest in this country.

After a little research, I was able to piece together the following timeline of the Black Freedman’s history from various sources (Gawd, I love the Internets!).

1863 – Cherokee Nation officially abolishes slavery; Some Cherokees who side with the Confederacy continue to hold slaves and fight against the Union in the Civil War

1866 – The Cherokees sign a treaty with post-Civil war US government extending Cherokee citizenship and enfranchisement rights to the freedmen and their descendants. The Cherokee Nation Constitution is amended to reflect the treaty’s language concerning freedmen’s rights.

1880 – The Cherokee Nation conducts a census to assist with the distribution of proceeds from sales of Cherokee land. Cherokee freedmen are excluded from the census and thereby, the distribution of proceeds.

1888 – US government passes An Act to secure to the Cherokee Freedmen and others their proportion of certain proceeds of lands.

1896 – US government commissions the Kern-Clifton roll to identify Cherokee Freedmen that were entitled to Cherokee land sale proceeds. The Kern-Clifton roll identifies 5,600 Cherokee Freedmen.

1902-1906 – The Dawes Commission, enacted by the US government, requires registration of American Indians. The Dawes Rolls classifies individuals as either: Indians by blood, intermarried whites, or Freedmen. Dawes commissioners generally listed all visibly black people as freedmen regardless of Cherokee blood ancestry that would have otherwise qualified some as ‘Indians by blood’. The Dawes roll lists 4,924 Freedmen.

1970s – Under pressure from Indian activists, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) begins to provide certain benefits, such as free health care, to members of federally recognized tribes. As citizens, Cherokee Freedmen are also eligible for benefits.

1983 – Ross O. Swimmer, then Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, issues an executive order requiring Cherokee Nation citizens to have a “Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood” (CDIB) card in order to vote. CDIB cards were issued by the BIA based on those listed on the Dawes Rolls as ‘Indians by blood’. Rev. Robert H. Nero and 5 other Cherokee Freedmen are turned away from polls when they attempt to vote in the 1983 tribal election.

1984 – Rev. Nero and his associates file a class action lawsuit on the basis of racial discrimination against the United States, the Office of the President, the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the tribal election committee, and Principal Chief Ross Swimmer.

1989 – The court rules against Rev. Nero and fellow plaintiffs, citing jurisdictional issues.

2001 – Bernice Riggs, a Freedmen descendant, sues the tribal registrar for citizenship based on blood ancestry. The Judicial Appeals Tribunal (now the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court) rules that Riggs adequately documented her Cherokee blood ancestry, but ultimately denies Riggs citizenship because her ancestors were listed only as Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls, not as ‘Indians by blood’.

2006 – The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court rules in favor of Freedman descendant Lucy Allen. The ruling concludes that acts barring Freedmen descendants from tribal membership are unconstitutional , since the 1975 Cherokee Constitution did not exclude Freedmen from citizenship, nor did it have a blood requirement for membership in the tribe.

And this is where the real fun begins.

After generations of being bounced back and forth between Cherokee and non-Cherokee statuses, the Black Freedmen finally regained their constitutional rights as Cherokee citizens in 2006. But before the Freedman could even get out a rousing refrain of ‘We Shall Overcome’, what happened?

The Cherokees changed the Constitution.

Damn.

In a series of political moves with dubious ethical connotations, high-ranking Cherokee leaders swiftly drafted a petition for a special election that would allow the Cherokee Constitution to be amended to exclude Black Freedmen as citizens. Despite accusations by some tribal leaders that signatures on the petition were forged, the required signatures were obtained, and in 2007, the Cherokee Nation voted to expel the Freedmen from the nation.

Double damn.

Advocates of expelling the Freedmen openly used racist rhetoric to rally voter support. In tribal leader Darren Buzzard’s 2007 email, he urged Cherokees, “Don’t let black freedmen back you into a corner. PROTECT CHEROKEE CULTURE FOR OUR CHILDREN. FOR OUR DAUGHTER[S] . . . FIGHT AGAINST THE INFILTRATION.”

Buzzard and others on his side of this issue contend that such inflammatory language is a matter of tribal pride, not racism. But proponents of the Freedmen cause, like professional genealogist and author Angela Walton-Raji, declared, “It is the blackness of the Freedmen descendants that is despised, NOT the love of those with Cherokee blood.”

And boy is that Cherokee blood valuable. Even Buzzard knows that. In his email, he also cautioned his Cherokee tribesmen, saying, “They will suck you dry.” The ‘they’ Buzzard referred to were the Freedmen. But suck them dry of what, exactly?

Maybe Buzzard was referring to the Cherokee Nation’s share in the 20-plus-billion-dollar-a-year American Indian gaming industry. Or maybe he was talking about the estimated $300 million of funds that the Cherokee Nation receives annually from the federal government. That’s right. Every year. $300 million. From your democracy-loving, tax-paying pockets.

Luckily, some folks at the Congressional Black Caucus pulled the Cherokee Nation’s card on trying to have its cake and eat it too. In 2007, Rep. Diane Watson of California and several other Black Caucus members introduced a bill that sought to sever the Cherokee Nation’s federal recognition, strip the Cherokee Nation of their $300 million-a-year federal bankroll, and stop the Cherokee Nation’s gaming operations if the tribe failed to honor the Treaty of 1866.

In other words, Diane counted coup on that ass.

The Cherokees’ reply to the bill was essentially, ‘Why are you picking on us, when everyone else is doing it too?’ The official response from then Chief Chad Smith claimed that the bill was “in retaliation for this fundamental principle that is shared by more than 500 other Indian tribes.” In a compromise between Congressional Black Caucus members and their American Indian counterparts, the bill was later modified to allow the Cherokee Nation to continue receiving federal funding as long as some settlement is reached in lawsuits concerning the Freedmen’s citizenship.

As of the writing of this post, at least one of those lawsuits is still pending, and will be heard in a Washington, D.C. court beginning Tuesday, September 20. Attorneys are asking a judge to restore voting rights for the ousted Cherokee Freedmen in time for the September 24 tribal election for Principal Chief. That lawsuit will mark another – and possibly the final – chapter in the Black Freedman of the Cherokee Nation’s fight for citizenship.

Yet even now, the brazenly exclusionary and racist dialogue regarding ‘outsider Indians’ continues. In a post dated June 14, 2011 on the Native American news and entertainment site Indianz.com, Wambli Sina Win, an individual who has held positions in both Native and U.S. legal systems, including Tribal Judge for the Oglala Sioux Tribal Court, an Assistant U.S. Attorney, and legal Instructor for the U.S. Indian Police Academy, writes why ‘Tribes should protect their Indian bloodline”:

“Have you ever seen a wild buffalo on its own, seek out another species with which to mate when there are other wild buffalo around? If the buffalo have sense enough to stay with its own kind, why is it so difficult for our young Lakota men and women…?”

“This was a choice by the minimum blood’s ancestors to breed the Indian blood out and to diminish the bloodline.”

“We don’t need parasites who contribute nothing to our people enjoying the benefits of what our ancestors fought and died to protect.”

Though Win’s treatise on racial purity doesn’t specifically mention blacks or the Cherokee Freedmen (ironically enough, her ire is directed mostly towards mixed-race White and Mexican Indians), it doesn’t take much of an imagination to infer that they probably aren’t excluded from her perceived threats to a pure Indian heritage. And clearly, her sentiments aren’t so shocking or outmoded that Indianz.com felt that their readers would be in the least offended by them.

But leaving issues of race aside, there are several other issues about the Cherokee Freedmen story that deserve serious scrutiny:

The Issues of Sovereignty and Democracy

The Cherokee Nation contends that the US government should have no say in who they decide to grant citizenship to, because they are a sovereign nation with their own government and laws and whatnot. A valid point. At least, it would be a valid point had the Cherokee Nation not shot itself in the foot on the issue of sovereignty when it filed lawsuits against individual Freedmen descendants in Federal court back in 2009. In doing so, the Cherokees willfully pierced the sovereign veil. So now the US courts actually do have a right to be all up in their sovereign business.

The Cherokees also argue that they should be able to change their Constitution. But their 1866 treaty with the US says otherwise. The treaty states that the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) must approve amendments to the Cherokee Constitution. The Cherokee voted a few years back to remove the requirement for BIA approval, but in a mobius-loop of logic, that vote isn’t valid unless the BIA approves the decision that it shouldn’t be able to approve such decisions. Yeeeah.

The Civil Rights Issue

The US has declared embargos, sung songs, and even gone to war against other sovereign nations that have committed similar acts of disenfranchisement and discrimination against their citizens. Not only are the Cherokees committing these acts, they’re doing it on US soil and they’re doing with $300 million dollars of annual federal funds. Now that’s gangsta.

The Moral Issue

Many members of the Cherokee Nation rightfully claim that America has a lasting moral debt to American Indians for effectively swindling them out of their lands using largely genocidal tactics; Yet, the Cherokee Nation is now attempting to skip out on the moral debt it owes – and previously agreed to pay – for the reprehensible and genocidal practice that was slavery.

Insert pot and kettle reference here.

The ‘Why Do these People Care?’ Issue

Actually, I’m not sure if this is an issue. But my Facebook friend who originally shared the MSNBC article posed this question to me:

“You ask great questions especially in regards to the Civil Rights aspects but I have a greater question, why would one group of people who were enslaved not only by Europeans but by these same native groups they want to cling too, want to be associated in any way with them? If you have no real cultural tie to them what’s the big fuss?”

As far as I’m concerned, a victim of oppression or injustice doesn’t need to have a good reason for wanting to not be oppressed or… er… injusticed. Yet if I wanted to speculate on a reason, I’d readily turn to Martin Luther King or W.E.B. DuBois and their respective debates with Malcolm X and Booker T. Washington on the issues of black integration during the Civil Rights and Reconstruction eras.

As far as I’m concerned, a victim of oppression or injustice doesn’t need to have a good reason for wanting to not be oppressed or… er… injusticed. Yet if I wanted to speculate on a reason, I’d readily turn to Martin Luther King or W.E.B. DuBois and their respective debates with Malcolm X and Booker T. Washington on the issues of black integration during the Civil Rights and Reconstruction eras.

But again, thanks to the amazingness of the Internets, I don’t have to speculate. I can get perspectives from those directly affected by the issue. Like this quote from a Cherokee Freedman who was interviewed in 1996 by anthropologist Circe Sturm:

“It is ridiculous to allow White people to take advantage of Indian programs because they have blood on a tribal roll a hundred years ago, when a Black person who suffers infinitely more discrimination and needs the aid more is denied it because his Indian ancestry is overshadowed by his African ancestry…. Either the descendants of freedmen should be allowed to take advantage of benefits, or the federal government, not these cliquish tribes, should set new standards for who is an Indian-and save [themselves] some money.”

…and this snippet from an NPR interview with Shonda Buchanan, a Freedman descendant whose visible blackness has gotten her harassed at tribal celebrations where mixed-race, lighter-skinned Cherokees were fully welcomed:

“It’s who I am. I don’t know, sometimes I feel like, you know, I’m going to sit at that counter. I’m going to drink out of that water fountain, you know? This is a heritage that my people have. And I wasn’t raised on a reservation, but I was raised knowing I was black and Indian.”

… or this perspective, appropriately listed under the heading ‘Why’ on the Freedmen’s website:

“It seems inconceivable that in the 21st century, anyone would have the concept that an individual with some African ancestry should only be able to claim that ancestry. This is not the case with other individuals of mixed ancestry; no one such as an individual with Chinese-Korean heritage or a Choctaw-Chickasaw heritage has to pretend he only has one lineage or should learn about one of his 2 heritages. The “one drop of blood concept”, obliterating all other ancestry only exists for people of African descent. Furthermore, many people of black-Indian ancestry have more knowledge of their Indian ancestors than their ancestors who lived in Africa or who originally arrived in the United States.”

***

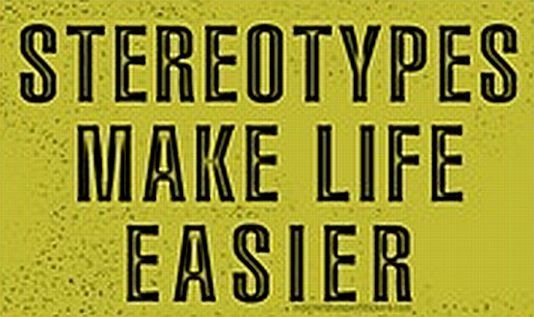

Most people prefer plots that are easy to follow. We like clear delineations of who is the good guy and who is the bad guy, and we especially like it if those delineations match our long-held perceptions of bad guys and good guys. It’s for this reason that most people seem to only be comfortable dealing with issues of race in terms of black and white. But the lingering spectre of racism – particularly institutionalized racism – is much more nuanced, much more complex today. In our allegedly post-racial society, we’ve at least identified if not done away with most of the glaringly racist issues concerning blacks and whites in the United States, but as they say, the devil’s in the details. There are a myriad of these ‘long tail’ racial injustices and race-based inequalities – like that of the racial wealth gap, or the troubling case of Troy Davis, or even the treatment of minorities in Europe as recently highlighted by London’s riots – that still remain and still deserve our attentions. But, rest assured, they will not be easy to fix. Mainly because the longer a sticky issue has been around, the harder it is to unstick once you finally do get around to fixing it. And these issues have been around for hundreds and hundreds of years.

guy, and we especially like it if those delineations match our long-held perceptions of bad guys and good guys. It’s for this reason that most people seem to only be comfortable dealing with issues of race in terms of black and white. But the lingering spectre of racism – particularly institutionalized racism – is much more nuanced, much more complex today. In our allegedly post-racial society, we’ve at least identified if not done away with most of the glaringly racist issues concerning blacks and whites in the United States, but as they say, the devil’s in the details. There are a myriad of these ‘long tail’ racial injustices and race-based inequalities – like that of the racial wealth gap, or the troubling case of Troy Davis, or even the treatment of minorities in Europe as recently highlighted by London’s riots – that still remain and still deserve our attentions. But, rest assured, they will not be easy to fix. Mainly because the longer a sticky issue has been around, the harder it is to unstick once you finally do get around to fixing it. And these issues have been around for hundreds and hundreds of years.

For now, the curious case of the Cherokee Freedmen issue remains unsolved, and the even curiouser questions keep pinging around in my little head:

How can the Cherokee Nation decide to be sovereign when it wants to make its own laws, but relinquish its sovereignty when it wants to use the US justice system to enforce Cherokee laws that are in direct opposition to the laws of the US?

How is it moral, ethical, or legal for the Cherokee Nation to give the Freedmen citizenship and then take it back when it’s more financially or politically convenient for them to do so?

You know, now that I think about it, there’s a term for people who do things like that.

But I won’t say it. ‘Cause that… would be racist.

cheers,

k

Want to get involved in the story?

Get more info on the September 20 Cherokee Freedmen trial

Follow the upcoming Cherokee Nation election

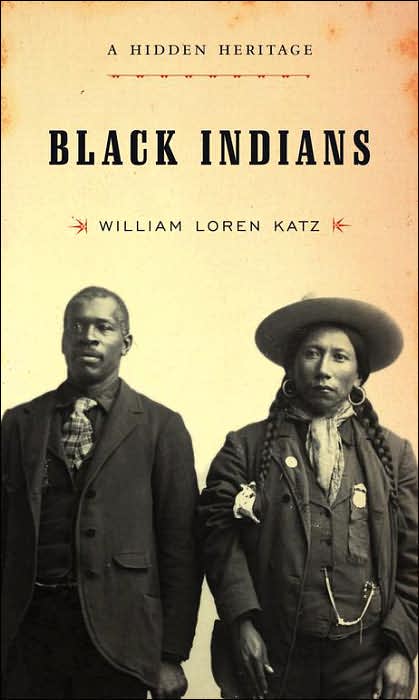

Read more about the history of Black Indians in the US

Thank you loved the article, do you know the current status of the Freedmen saga?

Thanks

Marcus